Memes, Meta Trends, Side-Parts & Skinny Jeans

The myth of generational war and the risk of millennial reactionaries developing into tomorrow's political grifters

Thank you for reading Digital Void! We release a weekly newsletter and podcast about digital culture, media, technology, politics, and memes. It’s free to subscribe and stay in touch.

Memes, Momfluencers, and Meta Trends

"Over the next decade language fluency will blur into media literacy.” - Matt Klein

We had the privilege of speaking with cultural theorist and CyberPsychologist Matt Klein for this week’s Digital Void Podcast. Matt, Jamie and I discuss his call to create a Rosetta Stone for Generation Z, the momfluencer aesthetic, 2021’s meta trends, and the reality filter of David Dobrik’s new Dispo app.

The Risk of Reacting to the Illusion of Generational Divides

Generational divides are constructs that distract people from important economic, social, and political issues.

In recent years, millennials have been the target of clickbait outrage campaigns ranging from Lay off the avocado toast if you want to buy house to Millennials are killing the restaurant industry (or, really, take your pick of industry). Similarly, baby boomers were subject of the dismissive and controversial, “OK, Boomer” meme. Generational wars are nothing new — activist Jack Weinberg famously coined, “Don’t trust anyone over 30,” in the ‘60s — but it’s all a distraction.

In Stop Mugging Grandma: The ‘Generation Wars’ and Why Boomer Blaming Won’t Solve Anything, sociologist Dr. Jennie Bristow writes about generational war waged against Baby Boomers:

The study found, in a nutshell, that feverish claims about the evil Boomers were really discussions about wider social and cultural issues: it was not a generational war, so much as a displacement activity for politicians and commentators running scared from the debates they really should be having.

Which brings us to the recent trend of millennial TikTok creators responding to anti-millennial sentiment. Millennial fashion staples like skinny jeans and side-parts are the most popular targets, but the cool/cringe factor of the 😂 emoji and whether-or-not Eminem should be cancelled are common topics.

Specifically, anti-skinny jean sentiment appears to be the most popular. Ryan Broderick details the trend in Garbage Day:

Is this all just a weird fake thing that was totally fabricated by old millennials working in various digital content factories? The answer is no, it was a thing on TikTok back in July. From what I can tell, it continued to circulate on the app until last fall. Anti-skinny jean sentiment then started appearing in news stories around November 2020. It’s mentioned in this Refinery29 piece. Then Dazed wrote about it a month later. I’m actually quoted in that piece! And then, finally, it truly blew up in the second half of January 2021. Yahoo! Financewrote a piece on January 15 titled, “We Called This Non-Skinny Jeans Trend Ages Ago and, Well, We Were Right” which is hilarious aggressively. And now it’s reached the Hamilton fan network graph.

Writing about the new millennial/generation Z “generational war” risks bringing unnecessary attention to a distracting issue. The reason why this trend is important is because of where it leads: Influencers building a brand based on artificially constructed intergenerational feuds. It starts innocuously enough (and even seemingly apolitical): Skinny jeans, hair parts, and emojis are not overtly part of polarizing economic, social, and political feuds. But skinny jeans, hair parts, and emojis are loaded with symbolic metadata that represent a pre-Covid, pre-Trump reality. A reality in which millennials are still young and Generation Z isn’t shaping popular culture.

Eventually, the symbolism of skinny jeans, hair parts, and emojis evolves into its own culture war. While this particular trend could end up as innocent as TikTok remixes of popular songs, engagement drives engagement. People who unironically agree that generation z is trying to influence millennial fashion choices or emoji use will be siloed together. The most popular social media platforms still run on the same incentive and operating systems that delivered us our hyper-polarized moment. Until incentives change, we shouldn’t expect results to change, either.

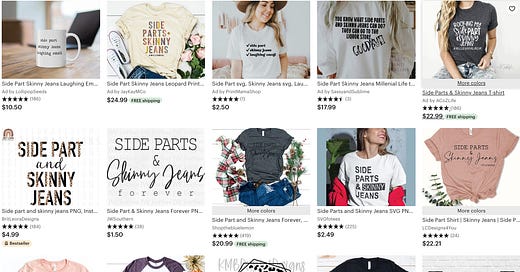

The most predictable route is that a handful of folks who receive critical backlash to their intergenerational videos learn to grift on reactionary content, toil in a reactionary cultural outrage space, and eventually migrate into political punditry. There’s already an Etsy grift industry attached to the “side-parts and skinny jeans” meme that borrows from the hyper-clean and well-produced aesthetic of momfluencers.

It’s important to be aware of how quickly communities can shift from apolitical to political. Ryan Broderick details how the Giggle Palooza meme page created in 2011 built an audience of 1.6 million followers based on apolitical memes — and a lot of Garfield — before it quickly turned into a far-right page that promotes anti-democratic and anti-mask content.

Community building engenders trust, and unsuspecting (but ideologically similar) folks are easy to target with disinformation and reactionary content. Taking this discourse as the intended joke it is — and not escalating or shaming reactionaries — is the only way to break the artificially manufactured outrage cycles.

- Josh